Comfortable: Dichotomy in Medicine

Dec. 5, 1986, Saving Laura’s Life, Part 3

Comfortable: The Dichotomy of Medicine

Dec. 5, 1986, Saving Laura’s Life, Part 3

Life changes in an instant. Once set into motion, things can spin out of control, like a chain of interrelated events happening simultaneously, or when a fan is turned on and it starts to spin faster and faster, and you are told to stay away from its blades. They will cut you and hurt you if you decide to put your hand there to stop it, I was told as a child. I would sit back and close my eyes or keep them open to watch the fan spin. Either way, something changes. The fan will create a wind that alters the air around it, to bring the promise of relief and improve your comfort level.

When I was a child, I was told not to touch the fan, not even the switch. Stay away! It’s dangerous! So I would sit and watch the blades spin slowly when the fan was first turned on, then observe it spin faster until I could hardly see each blade. Once cast into motion and turned to high speed, the individual blades don't seem to exist anymore. The only thing left is this fast and automatic repetitive motion, now a force of its own. It will make you comfortable, my grandmother used to say when she turned on the large standing fan in our living room, with its exposed metal blades and only a sparse grate to contain them. Safety and protection were uncommon in the early models. My siblings and I were simply trained to stay away from this ferocious spinning potentially harmful mass of blades in order to feel cooled off and soothed from the summer heat. The fan will make you more comfortable, she declared with confidence. At five years old I settled back onto the lower step of the staircase on hot days, as I watched and waited to feel better, to become cooler, or whatever was supposed to happen. I sat there and wondered, how can something that is meant to make you feel good, be so dangerous, that it could draw blood, and cut you, if you got anywhere near it. I sat there sweating and waiting to be more comfortable, as more uncomfortable feelings rose within me. She called out again to remind me. It’s dangerous! You will get hurt! Stay Away! I can still hear my Grandmother’s warnings.

****

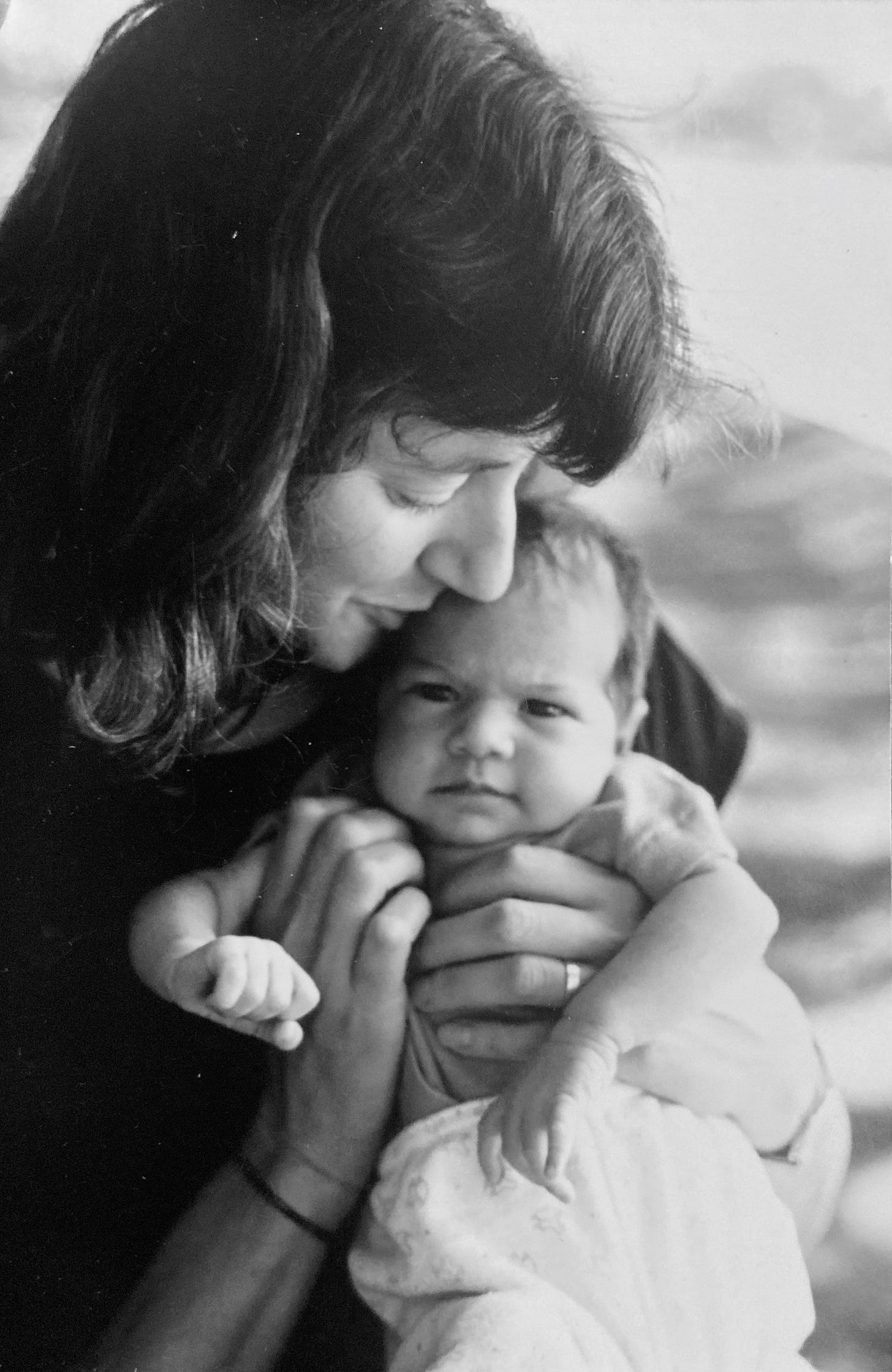

“The first thing we want to do is to make your daughter more comfortable,” Dr. Rome said to us right after he introduced himself as a cardiac fellow on Dr. Long’s team. “We will start by putting in an intravenous line, and IV. We will give your baby intravenous Lasix, a diuretic, that we will use to get rid of the extra fluid her body is holding on to. This will help Laura to breathe easier, and the profuse sweating that you've been seeing should start to diminish. The plan is to prepare Laura for a cardiac catheterization procedure. We hope to do that tomorrow, and then the open heart surgery, within the next few days. Dr. Long will be in to see you to explain all of this in more detail. Your baby is very uncomfortable. She has congestive heart failure. We have to help her out of this, and the sooner we get started on this plan, the sooner we can make your baby more comfortable.”

Dr. Long came into Laura’s hospital room where Paul and I were standing over the crib, each in a stupor of shock, both gazing down at sleeping, sweating, and rapidly breathing Laura. He asked us to please take some seats, so he could go over the plans for the procedure and surgery that were already cast into motion behind the scenes. I imagined that when the doctor looked at our weary and speechless faces, he must have known to cut through the specifics and just get to the point, to help us understand the direness of this emergent situation and insure our cooperation.

“If we don't do the catheterization and the heart surgery, specifically called Pulmonary Artery Banding (PAB) this week, your baby will die. Laura's been in congestive heart failure for some time now, we suspect probably since the opening in her heart, the patent foramen ovale (PFO) closed naturally at about three days old.”

As Dr. Long continued on, I strived to keep up with him. I heard him say something about the flooding of blue blood, or was it red blood, from this artery to that aorta, to one atrium and then back down to the left ventricle, which he emphasized she only had one of these, instead of two since the right ventricle was malformed and not pumping. He drew diagrams of Laura’s heart to show us what Laura’s heart physiology looked like, and what would happen in each procedure. We tried to follow what was being shown and told to us, but mainly only comprehending the gravity of the situation.

Dr. Long was holding a clipboard, then handing it to us while saying, “We will need you to sign this release to consent form for the catheterization procedure right away.”

Paul took the clipboard as we huddled together to try and read it. Dr. Long went over each item with us as we read along silently. I tried to read and listen at the same time. Saturated and overwhelmed from the doctor’s descriptions, my mind glazed over until it was snapped to an abrupt attention when he got to the part about the risks to our baby during the catheterization procedure; excessive bleeding, cardiac arrhythmia, infection, stroke and even death. “ I don’t want to alarm you with all of this. We are required to list the risks, but they rarely happen.”

My mind jumped to; he said rarely happened, not never happened. Paul and I looked at each other, as if we were thinking the same thing; that somehow we could choose to opt out, to escape the danger, until quickly realizing there was no choice. The cardiologist had made it clear to us that this was urgent, life and death in fact. The world was forcibly throwing us into this situation with a doctor who seemed to know what he was doing. He presented as caring and intelligent, so we signed the consent form and opened ourselves up to trust him, while still feeling that we had no choice.

This cardiac catheterization release form would become the first of a succession of way too many to count release forms that Paul and I would be beckoned to sign over the years. And so we did each time; dutifully and always reluctantly. Whichever one of us signed that first release form and handed it back to Dr. Long that day was not a detail I would remember. What I do recall, is that when he took the clipboard back, he flashed an expression that seemed to emote empathy toward us and a bit of triumph within himself, possibly indicating that he could never be sure a parent would sign it as quickly as he needed it to be signed.

If I am to be honest, I don't recall every medical detail of what happened now, next, before, or later. What my heart considered most memorable that day, was not necessarily the details of each medical procedure that was recited to us by doctors who spent years studying and practicing medicine. It was the emotional impact it had on us. In the early days of our baptism into Laura's medical drama, it was all just a series of dangerous blades threatening our baby's well being at each and every turn, disguised as something that would make her feel better, get better, and be better, to become more comfortable. How could cutting into her flesh, and breaking her sternum, when she was just a small and frail being make her more comfortable? This was the contradiction of medical intervention; that what the doctors trained for, and what we prayed for, would make Laura get better somehow if we allowed her to be touched by all those sharp needles, knives and blades. I was trained to stay away from danger, but now I was being called forth, to hand my daughter over to the doctors, to relinquish all control to this seemingly barbaric way to help Laura, not simply get better, but to stay alive.

Dr. Long looked at us reassuringly, “I want you to know that I will personally be doing Laura’s catheterization. It’s my area of specialty and I do them quite often, so not to worry. Your baby is going to be okay. Keep in mind this is just the beginning, the first step to getting your daughter well.” This may have been said to comfort us. Instead it made my heart go from trust to dread. It’s just the beginning? How could we bear more than this?

“OK, now that you have signed the release form, we will need you to get up and leave the room while we put in the IV. This is not something you can be in here for,” Dr. Long stated clearly.

Paul and I stood to attention in response to our new orders, though we resisted leaving the room right away. We peered into the sterile metal crib that held our soundly sleeping baby who would soon be abruptly awakened and stuck with a needle to thread an IV into one of her tiny veins. Laura’s face was covered by an oxygen mask to help her breathe better. There were several small disc-like patches adhered to her chest and belly with wires attached to them, that led to what we were told was a heart monitor mounted on the wall, continuously projecting a graph of Laura’s heart rhythms. Nothing has been painful so far. This would be the first invasive procedure. I began to visualize what was ahead for our baby, and I became flooded with imagery of Laura crying in pain without her mother or father there to comfort her. I pre-grieved the emotional and physical pain she would endure.

As we were being ushered out of the room, two nurses holding prep trays entered and hurried past us toward the crib. Dr. Long followed and stopped us outside of the door, “One more thing, no more nursing your baby. We will need to measure every once of her fluid intake going forward. You can express the breast milk and feed it to her in a bottle from now on.” This new information did not sink in yet. I was thinking about how I could negotiate a way to stay in the room with Laura. Paul turned to comfort me when he heard my desperate pleas to stay with Laura during the IV procedure, and saw how I was quickly told it was just not allowed.

"We have rules here and there really is no option,” one of the nurses barked out.

I wondered if I could simply cower in the corner of the room, like when I sat on the steps after my grandmother snapped at me to stay away from the fan, to not go near it, or touch it, making the moment agonizingly uncomfortable.

I turned to Dr. Long to petition my case, "Can't I just sit in the corner of the room. Laura has never been without a parent,” I said in a strong, calm, and desperate voice of a mother striving to protect her young, a request that I was sure no doctor could refuse.

"NO, not this time,” he said. "We will come and get you immediately when it is over. I promise.”

The doctor escorted us to the parent waiting room, far enough away from where we could hear our baby’s cries. Paul and I stood in the hallway embracing each other and bracing for what was to be the beginning; the first blade in a series of treatments that were now underway, cast into motion, and spinning into our new reality.

We were the children now, and the doctors became the ones in command; telling us what we could and couldn't do, and in charge of what our baby needed, instead of Paul and I making the moment to moment decisions for Laura like we had done during those first weeks and months of her life. It was now the job of the cardiac team at Boston Children's Hospital to call the shots and to be in charge of Laura’s care. As difficult as it was to stand on the sidelines, we knew that they were the ones who knew better, who could help Laura stay alive. We could only offer her love. Your baby will die without surgery. The doctor’s words were repeating in my mind, while we were standing in the hospital corridor, waiting together and holding intense fear in our hearts.

We balanced feelings of gratitude to those who could save Laura, with the terror of something going terribly wrong. We were being asked to place our trust in this cardiac medical team, just as we were asked to trust our first pediatrician, and then our second one. We had no choice. Our destiny had changed. We were to share the parenting of Laura from that point on. We surrendered and gave the doctors our trust.

A new life was being put into motion. The medical information was spinning too fast for us to keep up with. Danger lurked everywhere in the form of needles, scalpels, and tubes. Like the blades of the fan, we could not see them as separate, but as a quagmire of threats, with Laura at the center, out of our protective sight, caught up in this fast moving cycle, the medical system.

Paul and I were told to stay away. Our baby would be submitted to medical procedures that would bring her suffering with the goal of making her more comfortable. Laura would have to endure being uncomfortable in order to become comfortable. This was a dichotomy in medicine; danger with a promise.

Thank you so much Jeannie! You are so generous with your time and comments. Thanks for being specific. So rare to get a comment like this. I want you to write my testimonial/ endorsement when I publish my book. I have to start thinking of how to go about staring that daunting process. Maybe the morning pages will help! Hope yoga training is wonderful for you! ♥️